The energy from the sun that hits the Earth in a single hour could power the planet for an entire year, according to the US Department of Energy (DOE). One of the best places to harness that free, abundant, and environmentally friendly energy is a desert, but deserts, it turns out, come with a nemesis to solar panels: sand. The particulate matter that constantly blows across deserts settles on solar panels, decreasing their efficiency by nearly 100 percent in the middle of a dust storm. The current solution is for solar field operators to spray the dust with desalinated, distilled water.

“That might not sound like a big deal, but if you have millions of square feet of solar panels out in a desert, it ends up being costly—especially if water is a scarce resource,” says John Noah Hudelson (ENG’14), one of several graduate students working to find a better solution with Malay Mazumder, a College of Engineering research professor of electrical and computer engineering and of materials science and engineering, and Mark Horenstein, an ENG professor of electrical and computer engineering. “We’re looking to use just a small amount of electricity to statically push the dust off the surface of the solar panel or the solar mirror.”

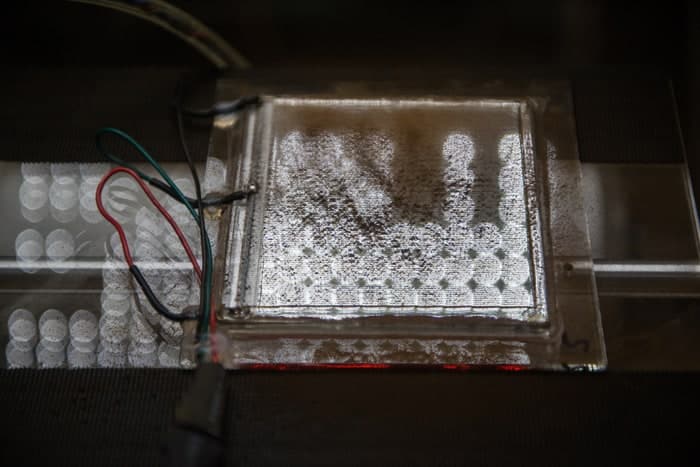

The BU team’s answer, called a transparent electrodynamic system (EDS), is a self-cleaning technology that can be embedded in the solar device or silkscreen-printed onto a transparent film adhered to the solar panel or mirror. The EDS exposes the dust particles to an electrostatic field, which causes them to levitate, dipping and rising in alternating waves (the way a beach ball bounces along the upturned hands of fans in a packed stadium) as the electric charge fluctuates.

The entire process takes seconds and uses a minuscule amount of power, generated by the solar device itself—about 1/100th of what it produces daily. In its final version, the EDS will be programmable or will automatically detect the presence of surface dust and switch on. “There’s nothing like this on the market,” Horenstein says.

The inspiration for the EDS came to Mazumder more than a decade ago from an unlikely source: human lungs. He remembers thinking that the organs, outfitted with self-cleaning hairs that sweep dust up and out of the respiratory system, were “ingenious defense mechanisms.” He thought he could mimic that tidy biological system and apply it to other mechanisms.

In 2003, NASA, whose scientists thought the technology could be used on future Mars missions to keep equipment free of cosmic dust, gave him a three-year, $750,000 grant. When that funding expired, a $50,000 Ignition Award from BU’sOffice of Technology Development kept Mazumder’s research afloat while he searched for alternative funding. His big break came in 2010, when he gave a presentation on the EDS at an American Chemical Society conference in Boston. News of the technology spread through articles in such publications as the New York Times and the Britain’s Daily Telegraph.

“There’s nothing like this on the market.”

—Mark Horenstein, ENG professor of electrical and computer engineering

Mazumder received a call from David Powell, a research and development manager at Abengoa Solar, a global pioneer in the construction of CSP (concentrated solar power) and PV (photovoltaic) power plants. The company operates the Solana Generating Station in Gila Bend, Ariz., and the soon-to-open Mojave Solar Project near Barstow, Calif. Each has the capacity to produce 280 megawatts—or the ability to power more than 100,000 homes. With at least two plants in desert locations, Abengoa was keenly interested in the success of the EDS and eager to test Mazumder’s prototypes.

In 2012, Mazumder and Abengoa landed a two-year, $945,000 grant from the DOEOffice of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy to further test and expand the capacity of the EDS. Horenstein and Nitin Joglekar, a School of Management associate professor of operations and technology management, are co–principal investigators of the grant, and Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, N.M., signed on to help evaluate the prototype’s efficiency and develop larger-scale models. With a $40,000 grant from the Mass Clean Energy Council, the team’s total funding rose to nearly $1 million.

For two months last year, Hudelson and doctoral candidate Jeremy Stark (ENG’14) tested nearly 20 EDS prototypes at the Abengoa and Sandia sites before rain and snow cut their work short. They found that the system performed as expected, removing at least 90 percent of dust particles from solar panel surfaces. Next, the BU team must figure out how to protect the EDS from Mother Nature and to upscale to industrial-sized models.

Mazumder estimates that the United States would need to produce one terawatt (one trillion watts) of solar power to meet household and industry demand. That kind of output is a distant goal, but he sees great potential in getting started by building solar plants in the Southwest—specifically the Mojave Desert. The arid region has an elevation of nearly 5,000 feet, receives regular sun, and has fewer dust storms than other desert regions.

“The Mojave Desert and the Southwest, if fully utilized and assuming the existence of a reliable distribution system,” he says, “could provide most of the US demand with respect to our energy needs.”

Mazumder will submit a proposal soon to the DOE for renewed funding, but he must first identify a manufacturing partner willing to produce industry-scale panels equipped with EDS technology. Once that goal is reached, he thinks, the self-cleaning system could hit the market after two years.

“We must proceed fast,” he says. “The need is there.”

Story and video courtesy: BU Today, Boston University